Caviar’s Secret Sister: Forgotten Garum (Ancient Fish Sauce)

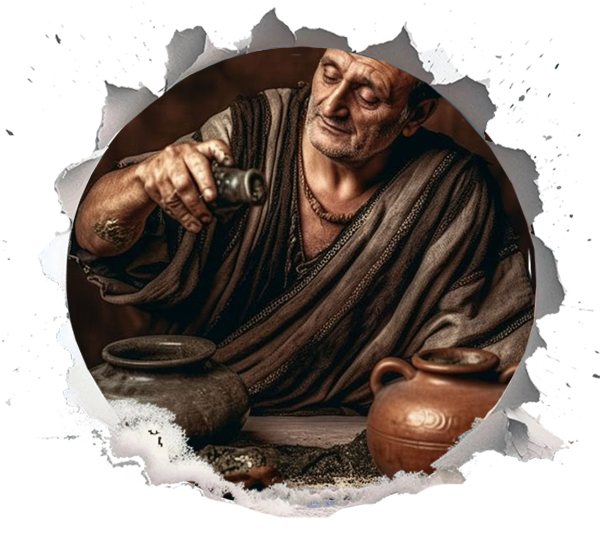

In the pantheon of luxury foods, caviar holds a storied place, celebrated for its delicate texture and briny sophistication. Yet, its lesser-known counterpart from antiquity, garum, offers an equally fascinating tale of culinary innovation, cultural influence, and timeless umami. Garum, the fermented fish sauce that fuelled the palates of ancient Rome, holds a unique place in culinary history. Once as ubiquitous as ketchup is today, this pungent condiment shaped Mediterranean cuisine for centuries.

This ancient fermented fish sauce, a cornerstone of Greco-Roman gastronomy, shares with caviar a legacy of exclusivity and craftsmanship—though their stories diverge in method and flavour. While delicacies like caviar have endured as symbols of luxury, garum faded into obscurity—only to resurface in modern kitchens. Here, we explore garum’s forgotten history, its intricate production, and its enduring echoes in modern cuisine.

The Rise of Garum: A Mediterranean Obsession

Origins and Cultural Significance

From Greek Gáros to Roman Obsession

Garum’s story begins in ancient Greece (circa 5th century BCE), where it was called gáros—a pungent sauce made by fermenting small fish like anchovies, mackerel, or sardines. Initially, it served as a practical method to preserve fish and utilize scraps. By the Roman era (1st–3rd century CE), garum transcended its humble origins, evolving into a culinary cornerstone. Its adoption by the Romans was no accident: as their empire expanded, so did their appetite for bold, portable flavors to enhance their grain-heavy diet.

Social Stratification in a Bottle

Garum’s role mirrored societal hierarchies:

- Elites: The wealthy indulged in garum sociorum (“garum of the allies”), a premium variant from Spain’s Cartagena coast, prized for its clarity and complexity. It was drizzled over dishes like ostrich stew or honey-glazed dormice, as recorded in Apicius’ De re coquinaria (the oldest surviving Roman cookbook, 4th–5th century CE). This type of garum was almost the same as Beluga caviar among people.

- Masses: Lower classes consumed garum muria—a cheaper, saltier version made from fish offal. Soldiers carried it as a protein-rich seasoning, while slaves ate allec (the leftover fish paste) as a spread.

Cultural Dichotomy: Praise and Scorn

Garum’s ubiquity sparked debate among Roman intellectuals:

- Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) praised it as an “exquisite liquid” in Naturalis Historia, noting its medicinal use for dog bites and ear infections.

- Seneca, the Stoic philosopher, condemned its “putrid stench” as emblematic of Roman decadence.

This tension reflects garum’s dual identity: a symbol of refinement and excess, much like truffles or blue cheese today.

Production: From Gut to Glory

The Science of Fermentation:

Garum’s magic lay in autolysis: enzymes in fish viscera (like intestines and livers) broke down proteins into amino acids, particularly glutamic acid, the compound responsible for umami. Salt (a 1:8 fish-to-salt ratio) acted as a preservative, inhibiting harmful bacteria while allowing beneficial microbes to thrive.

Industrial-Scale Craftsmanship:

Production occurred in coastal factories (cetariae), notably in Spain, Portugal, and North Africa:

- Fermentation Vats: Fish layers alternated with salt in large clay pots (dolia). These were left under the Mediterranean sun for 2–3 months, stirred occasionally. The mixture liquefied into a pungent slurry.

- Straining: The slurry was filtered through woven baskets, separating:

- Liquamen: The prized clear, amber liquid (the “first press” of garum).

- Allec: Thick sediment used as a paste or animal feed.

- Variants:

- Haemation: A luxury version made from tuna blood and organs, fermented with wine or herbs.

- Quick Garum: A budget-friendly method involving boiling fish in brine with oregano or thyme.

Logistical Challenges

- Salt Balance: Too little salt led to spoilage; too much halted fermentation. Roman producers mastered this ratio through trial and error.

- Odor Management: Factories were built downwind of cities (e.g., Pompeii’s Garum Shop), as the stench of rotting fish was overwhelming.

Economic Powerhouse

Garum became a Mediterranean-wide commodity. Spanish factories exported it in amphorae stamped with producer names (e.g., Flos Garum, “Flower of Garum”). A single workshop in Baelo Claudia (Spain) could produce 1,500 liters annually, shipped as far as Britain and India.

Garum’s Legacy: Parallels and Contrasts with Caviar

Shared Prestige, Divergent Paths:

Like caviar, garum was a marker of status. Garum and caviar history was tied together in a period of time. Garum sociorum from Spain’s Cartagena fetched astronomical prices—four amphorae cost a legionary’s three-year salary 3. Both products emerged from resourcefulness: caviar preserved sturgeon roe; garum transformed fish waste into gold. Yet their paths diverged sharply.

- Caviar: A luxury of preservation, relying on salt-curing roe without fermentation.

- Garum: A product of controlled decay, harnessing fermentation to extract depth from scraps.

The Role of Umami:

Both foods owe their allure to umami, but garum’s glutamates made it a versatile flavour enhancer. Romans used it to elevate stews, sauces, and even desserts—akin to how chefs today employ soy sauce or fish sauce. Modern analyses of Pompeian garum residues reveal its protein-rich profile, akin to Vietnamese nuoc mam.

Decline and Rediscovery: From Ruin to Revival

The Fall of Garum:

The collapse of the Roman Empire spelled garum’s demise. Salt taxes and pirate raids crippled production, while shifting tastes favoured simpler seasonings. By the Middle Ages, it survived only in Byzantine kitchens and Arab murri (a cereal-based sauce).

Modern Resurrections:

Today, garum is experiencing a renaissance. Archaeologists and chefs alike are resurrecting ancient recipes:

- Flor de Garum: A Spanish team recreated Pompeii’s sauce using anchovies and herbs, yielding a briny, herbaceous umami bomb.

- Noma’s Innovations: René Redzepi’s lab ferments ingredients like mushrooms and chicken wings with koji, mirroring garum’s enzymatic magic.

- Colatura di Alici: Italy’s answer to garum, this amber anchovy sauce from Campania is drizzled over pasta, echoing Roman traditions.

Conclusion: A Sauce for the Ages

Garum’s story is one of transformation—from humble fish guts to a culinary linchpin. Its revival underscores humanity’s enduring quest for depth and complexity in flavour, a quest shared by caviar aficionados. While caviar whispers of icy rivers and royal banquets, garum murmurs of sun-baked Mediterranean shores and bustling Roman markets. Together, they remind us that luxury is not merely in the ingredient, but in the artistry of its alchemy. For those eager to taste history, a dash of colatura or a drop of modern garum offers a portal to antiquity—a testament to the timeless allure of fermented fish.